NaNoWriMo 2023 – Part III: Creative Process

This is the third part of my reflection on NaNoWriMo 2023, commenting on how my real life unfolded throughout the month as I was writing the story. It’s more meta talk about NaNo rather than its content, and so probably the most interesting one out of them all.

2023’s theme, unlike previous years where the story was based off a concept or idea, was instead about writing something inspired by one’s own experiences. This is why I’ve decided to talk about how the characters and settings for this story related to my own events and observations in life, both of which you can check out.

Story Planning

2023’s story synopsis, like most other years, reads more like it was written for a series than a novel. It’s something I didn’t consciously intend, but rather gravitate towards. I think the reason behind it is that it’s impossible for me to know how the entire story will unfold.

It also makes it very clear that I’m not an outliner, as much as my young self saw the benefits of such a method of writing and tried aspiring to aim for. Just like finding your vocal style, writing paradigms should never be forced.

After all, you don’t choose to pants. The pants chooses you.

Planning Templates

Still, some kind of outlining is better than none. Ideas came throughout the year starting at the top-level as I worked my way down. Here’s how 2023’s story came to fruition, from thought to screen, step by step:

- Start of year thought: Female main character carrying out her work, having casual/joke/shitpost lively banter with workmates and friends. The idea began with specific speech lines in mind. “Hell’s he doing in the middle of the road like that…?” “Don’t worry, let ‘im cook. Promise you’ll see at the end.” Then, I’d build a rough sense of what those characters would’ve been, what they were in, and work outwards.

- Triple five:

- 5 sec: I didn’t get to figure out my elevator pitch.

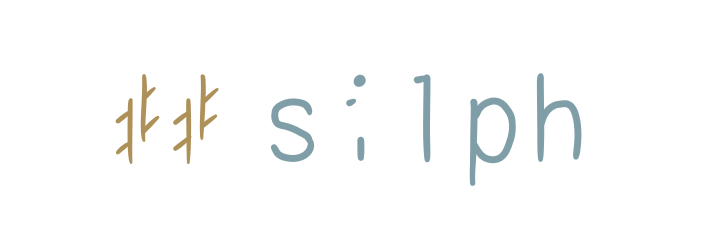

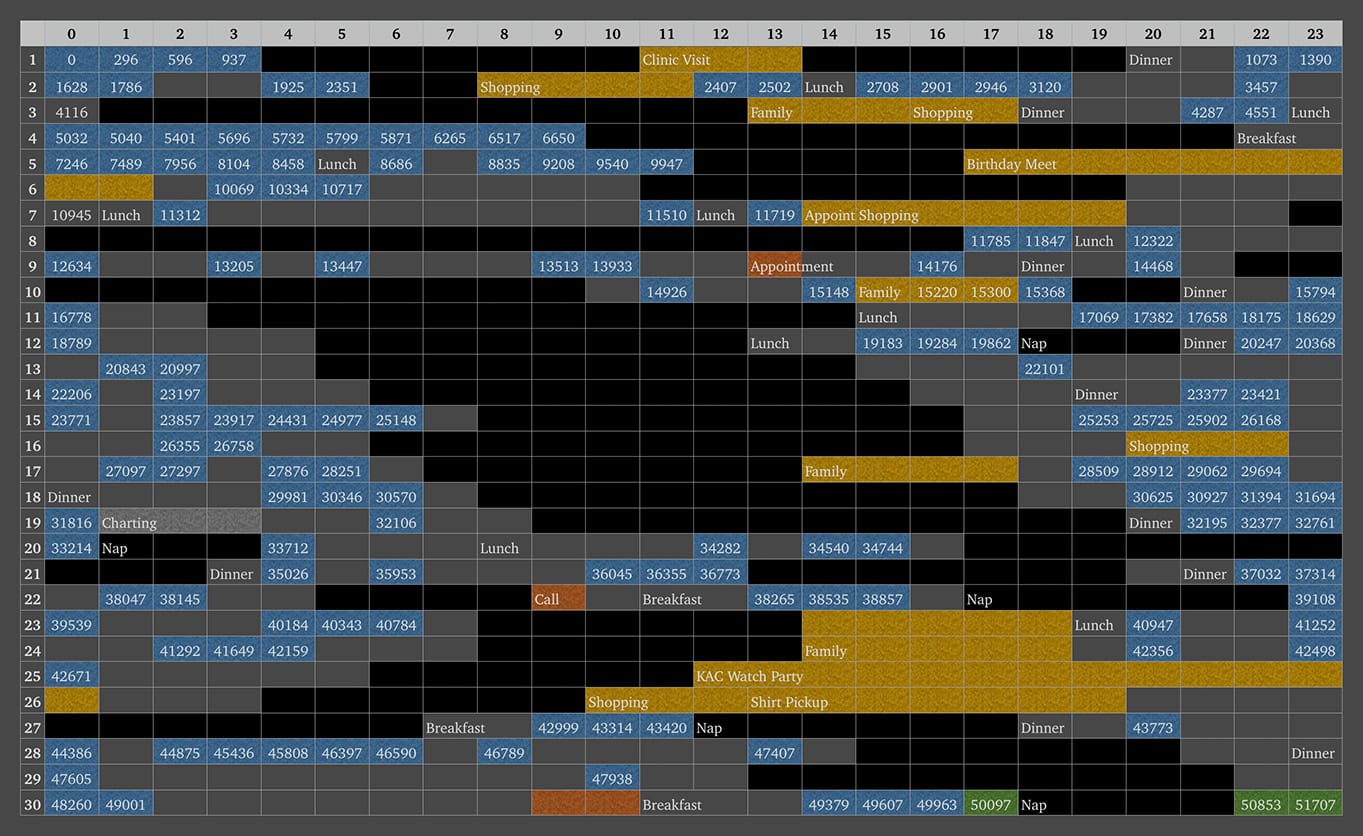

- 50 sec: I worked on this instead, to arrive at a summarised, five(ish) sentence long, three act structure. I also wrote some notes whilst I was at it, so this was less of a paragraph and more of a table. It was written in the iPad’s native Notes app [Pic 1, below].

- 5 min: I then transferred the 3AS over to Scrivener, each sentence being a folder, and parked it there.

- All other notes: I continued to develop in Notes. This was stuff like character profiles, story world, and other bits of research or high IQ complex concepts I had to keep in mind. Whilst I was very aware that this is possible in Scrivener, Notes felt more ‘immediate’ to me.[1]

- Save the Cat: By this time, it was about a week out from November. A few years back, I came across the rather specific story structure of Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat (you’ll have to search this one up yourself, sorry), and have used it as a guideline to assign word counts to each of the five parts in the 3AS. The percentages in brackets are the values specified, the word counts my own plan:

- Intro (0–10%): 5k

- Act I (10–20%): 5k

- Act II (20–80%): 30k

- Act III (80–99%): 7.5k

- Ending (99–100%): 2.5k

- Scene list: Within each folder, I would then brainstorm scenes with lengths in rough multiples of 500 words – not just because it’s a nice, short amount that’s easily possible to sprint in a writing session, it’s so that I can assign 100 “slots” to the story, i.e. each covers 1%, making it easy to correlate 1:1 the percentages in Save the Cat’s structure. Each scene can be likened to a collection of shots in a film, of which there are also usually around 100 (barring long takes, which arguably still consists of multiple shots or scenes, just not interrupted). Some example guidelines for my stories:

- The introduction teaser, and perhaps a cliffhanger epilogue, is worth at most two slots.

- An instance of an action scene from start to finish I feel generally lasts five to ten slots.

- Interludes between action scenes (moving from one place to another, preparing, etc) can be anywhere from one to four if it doesn’t involve some kind of side story.

- Side stories by themselves take up around ten. Slice-of-life or abstract settings like dreams I tend to find considerably easier to write, so they naturally end up taking even more than that.

- The finale, if I actually get to them, I picture being around seven-ish.

- ‘Character routes’ in my past stories generally span around 10 to in excess of 20 before the fun starts. For whatever reason, they’re always a singular chapter, with time progressions only ever necessitating section breaks.

- Interestingly, visual novel-style erotica scenes commonly take up, bare minimum, 7–10.[2] “Sleep inducing” is a popular critique of these scenes, because they often focus on physical descriptions (which works beautifully with illustrations, but immensely boring to read) rather than emotional (more space to creatively elaborate, but impossible to implement visually).

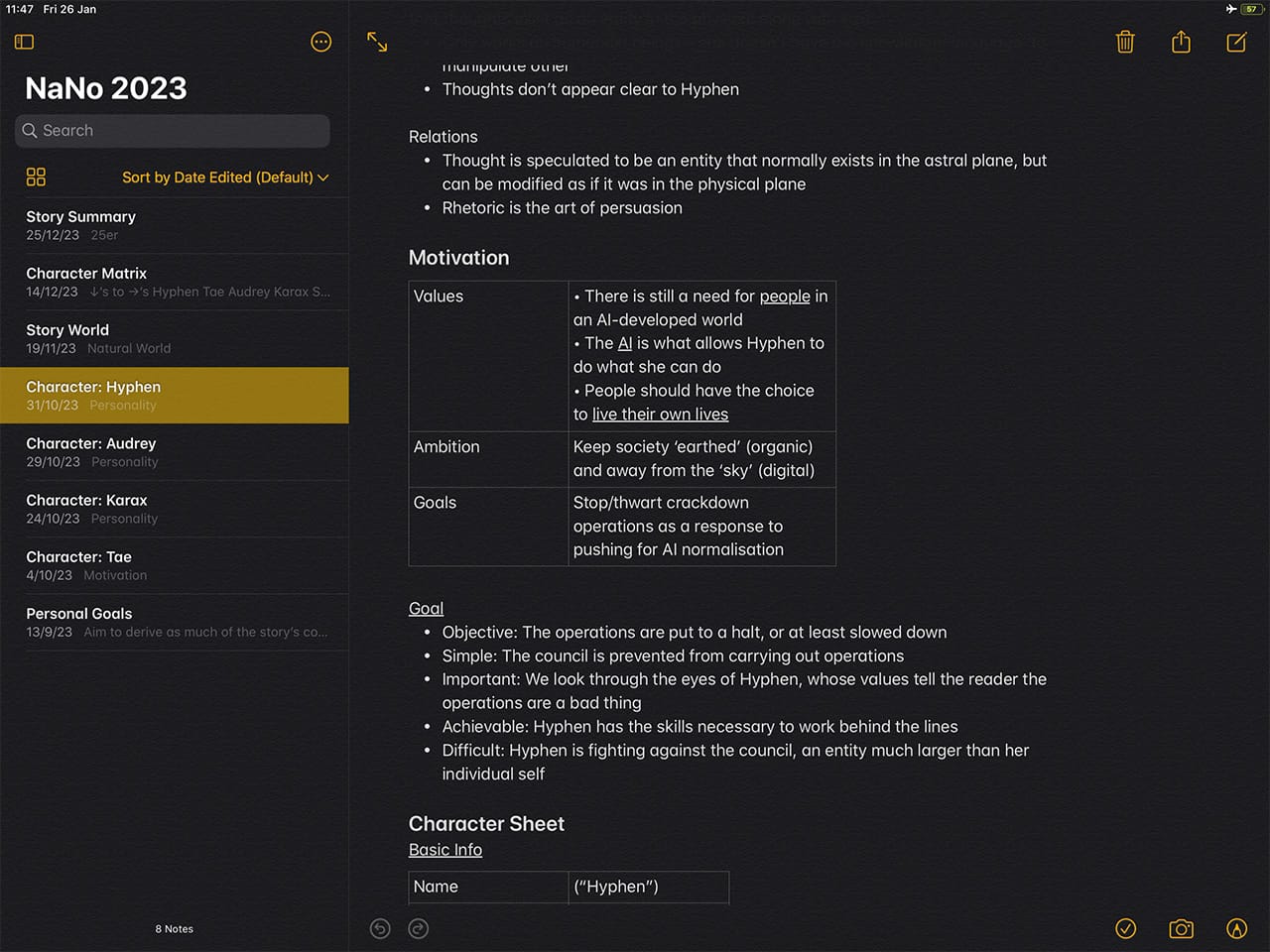

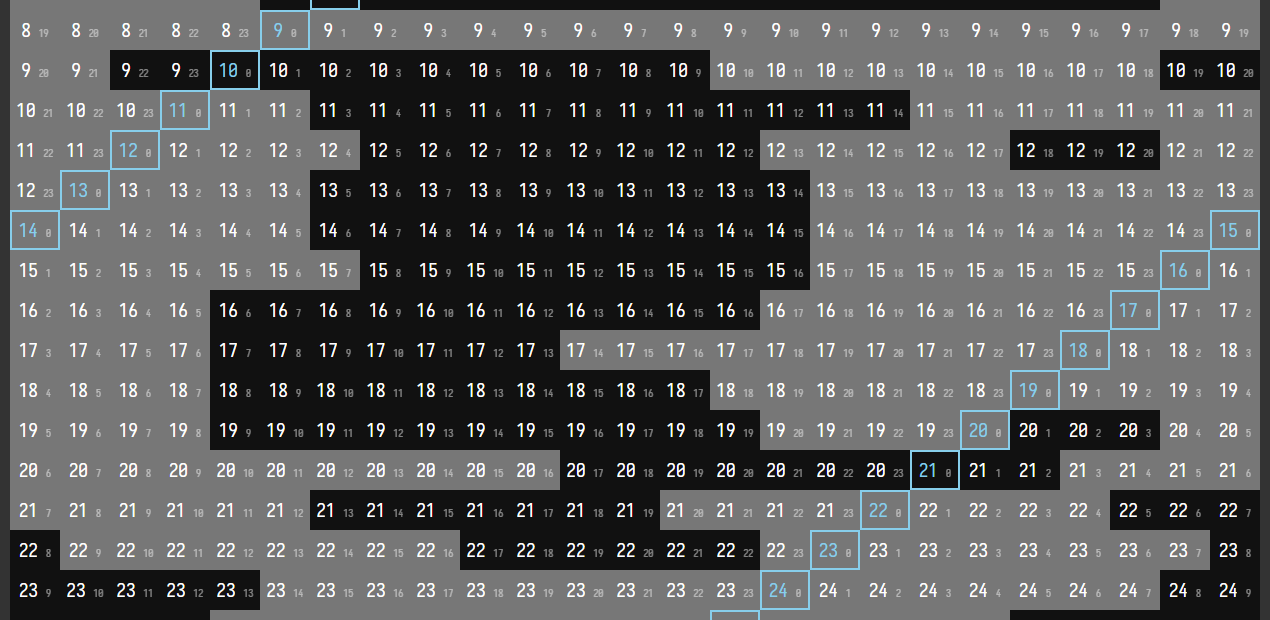

- Organisation: Working in Scrivener, a summary for each scene is written in the synopsis field of their documents, along with my predicted word count. At this time, I also begin noticing how the actual story is starting to piece itself together. When something doesn’t work, this is where I can rearrange scenes, or split them if necessary; an intuitive feature that a spreadsheet simply can’t match in terms of UX [Pic 2].

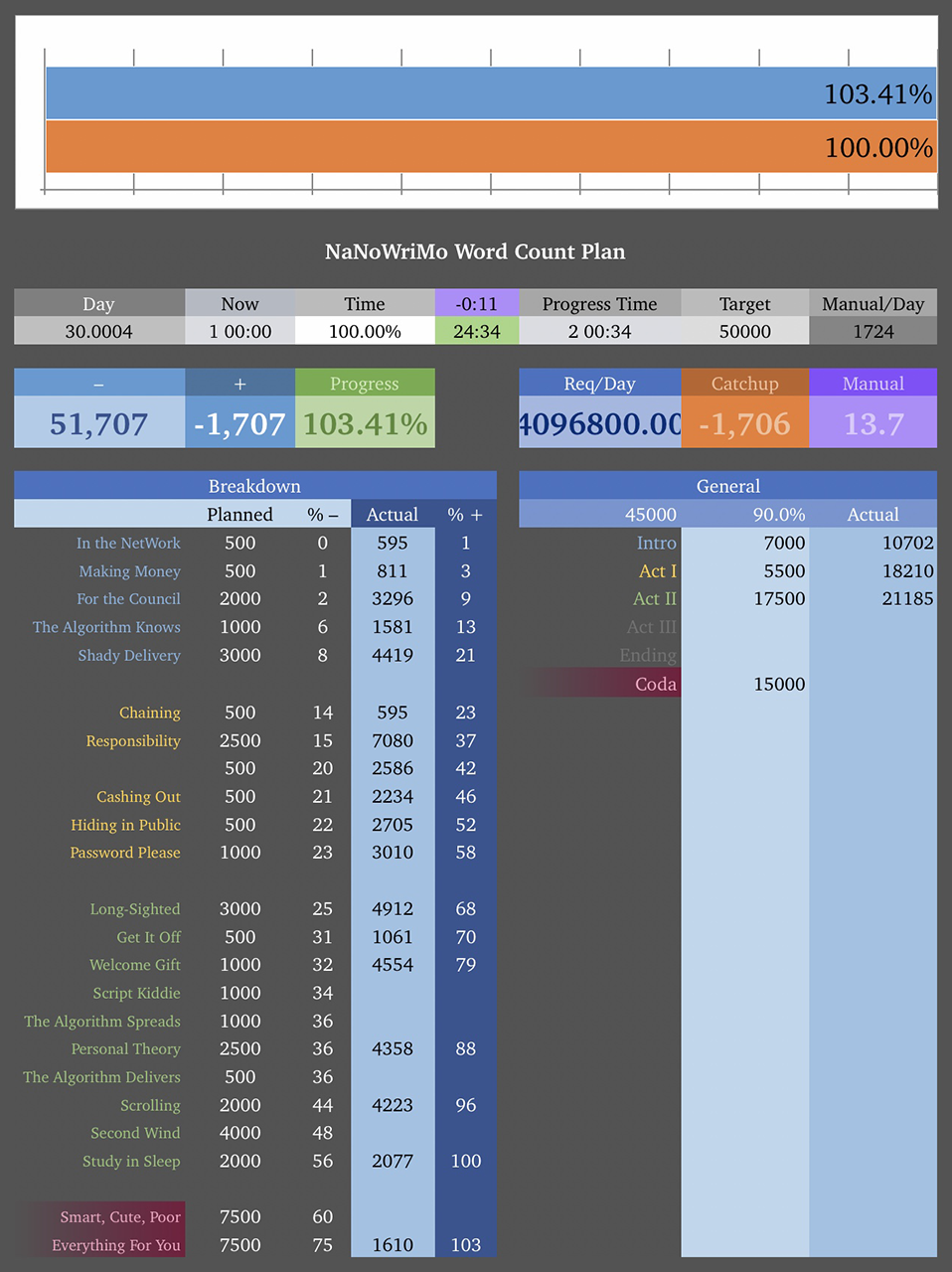

- Spreadsheet: Once I’m happy with the order, I can then transfer these chapter names and word counts to my spreadsheet.

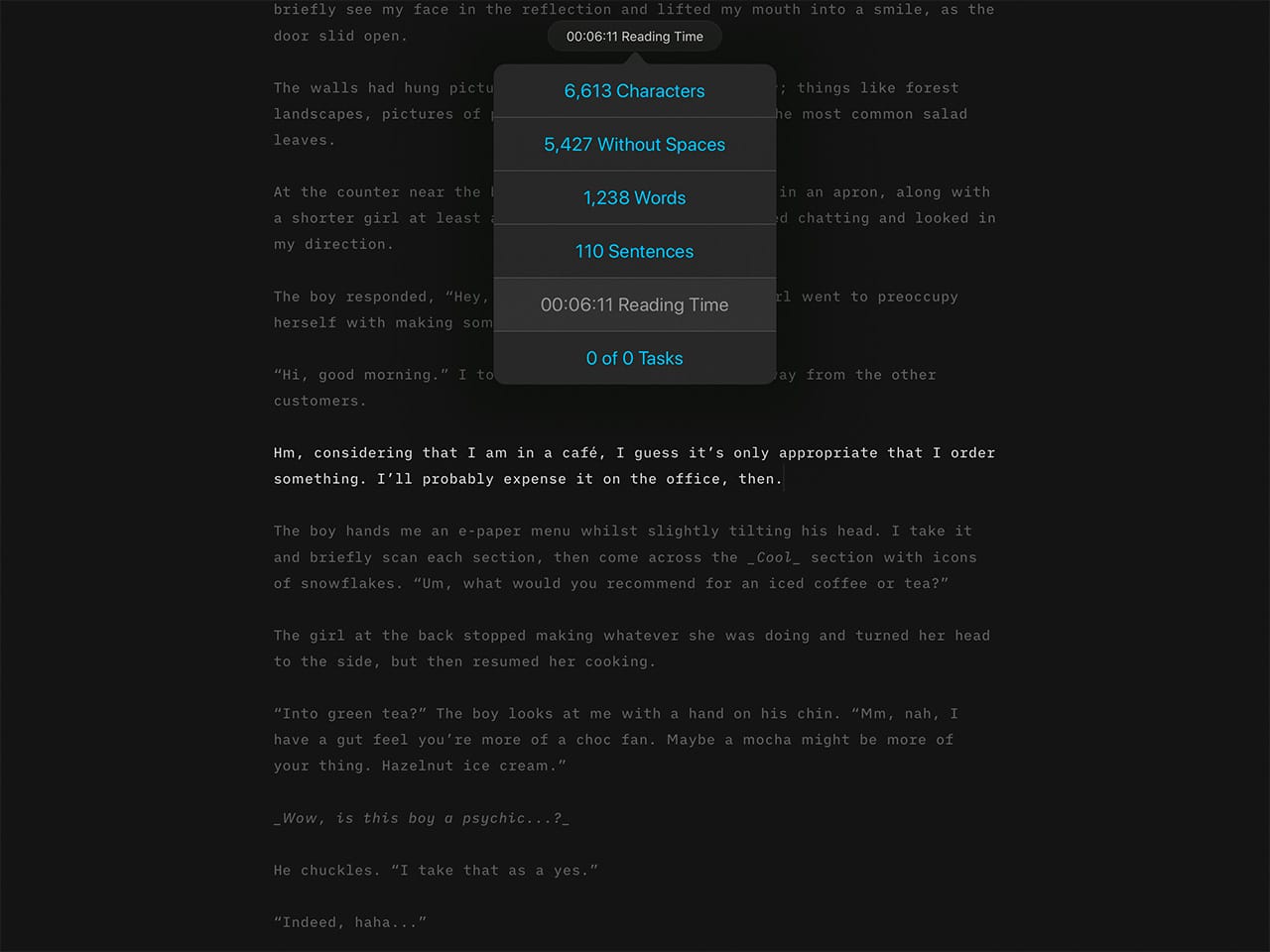

- Begin writing: In this project, I wasn’t able to actually complete organising the scenes before November came around, so I started writing with what I had. Instead of using the heavyweight Scrivener, I used iA Writer, for a fair few reasons – all of which are illustrated in [Pic 3]:

- It fits my usual flow of writing in Markdown and having each chapter as a file rather than an abstract document in a project.

- It has reading time as an alternative to the exact word count. This metric can still serve its purpose of denoting progress, just not in a way that I can trivially translate to the golden number of progress.

- Typewriter scrolling (page automatically scrolls such that the cursor’s current line is always at the centre).

- Focused, full-screen writing. ‘Focus’ as in things like current paragraph/sentence/word highlight, hidden UI elements, etc.

it sounds so backward using a suite of apps to get the job done (see: sai/csp lineart → photoshop colouring), but best of every world, I guess…

Whether I followed this plan during November in regards to word counts, well, uh… we’ll get to that when I talk about the spreadsheet.

Reason/Purpose of Each Scene

It should be noted that during the stage whilst I’m planning and rearranging scenes within Scrivener, each (okay… *most, as evident in the screenshot) synopsis starts with the reason why that scene is where it is. I find this helps me in a fair few ways.

Know your ‘tell’

You know the saying: show, don’t tell (and do it responsibly). Though sometimes, when you’re busy showing the details word-by-word, you forget what your original point – the take away you wanted your reader to imply – was supposed to tell.

So... write that down. That’s the reason, or purpose, of the scene. For me, knowing what it is, and reviewing it when I’m writing, helps keep me on track with the story.

Debug logical errors

Totally unintentional word choice aside, a side effect of understanding your scenes’ reasons is that you may begin realising some of them are at conflict.

There was a collection of chapters I had where Hyphen was lined up to be at a few places in succession back-to-back, order being evening → night → morning → afternoon; she was to pick up some cash from an ATM in the evening, only to realise it was out of service, and instead spend the night completing a job on the other side of town before heading straight back home. If I was to postpone the ATM cash out scene to the next night (time of day important), it still leaves the question “then why couldn’t Hyphen have just gone back to the ATM in the morning, instead of leaving it until night, if it was that urgent”.

These scene reasons reveal to me the extent of how far I could move them around (due to timeline/plot/other limitations), and what I had to patch up if doing so still wouldn’t resolve the problems.

Have I seen you somewhere before…?

Naturally, a part of these logical problems include introductions to places, people, or concepts (rules you and the reader have established, e.g. “a w can only have x y’s per z”).

If Tae was meant to first show up in Password Please, which makes the most sense if he was at his café, I can’t have him nor the café be descriptively mentioned before that chapter.

Even if we break the rules a bit and introduce something via a teaser, that teaser still has to very much look like one. Almost always, that involves a change of tone to something more hyped.

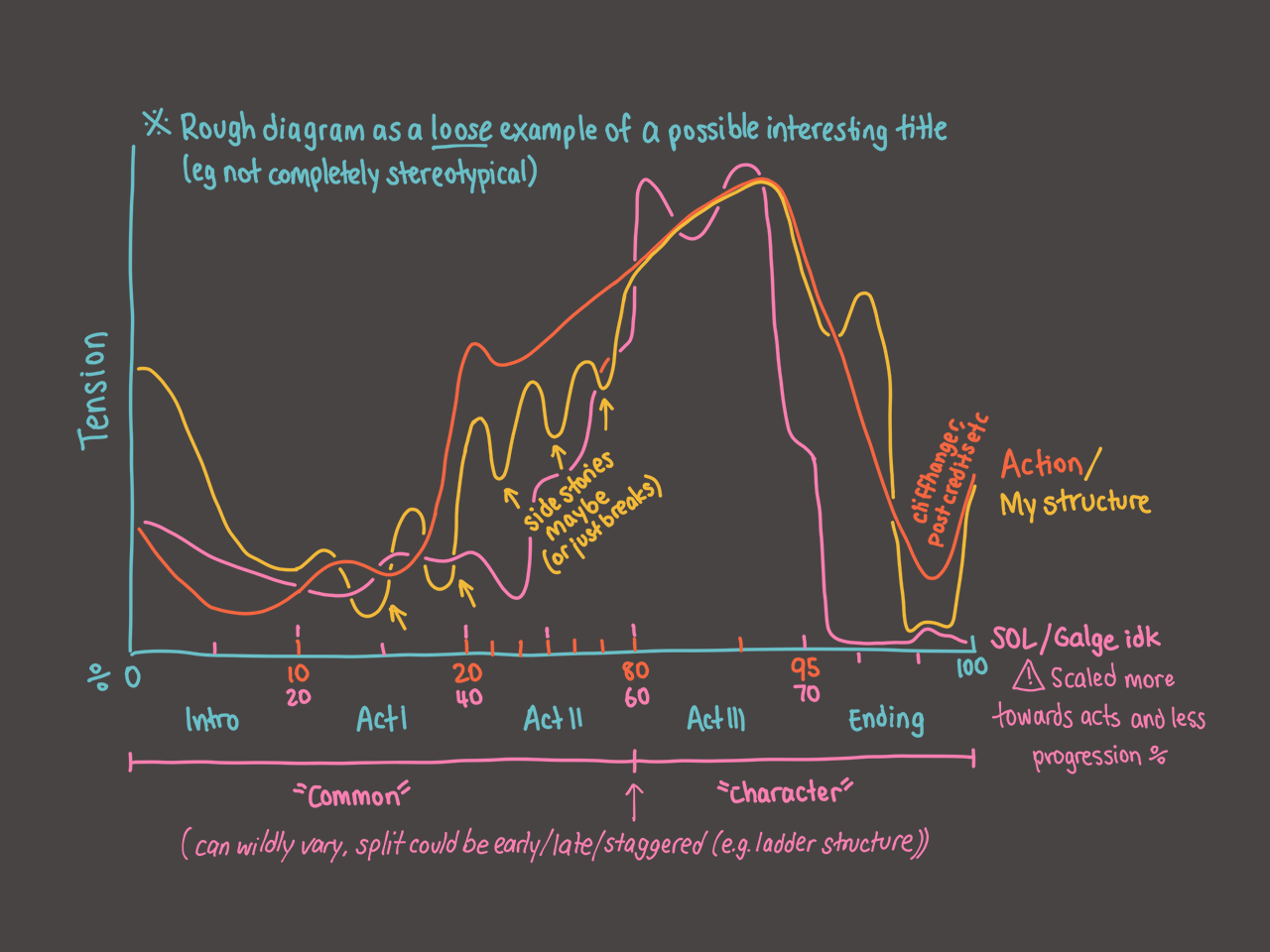

Controlling the tension waves

Each reason in a scene can also be used as a categorisation to check if it belongs in your main storyline (i.e. it advances it further in some way), or your side or character ones (i.e. it’s there ‘just because’).

With my stories, I like to follow an even split of both that roughly alternates (main → side → main → side, etc) to control and pace the story’s tension.

Compare this pacing to say, an action thriller (vast majority main, and the tension increases without a drop from start to finish) or a slice of life drama (majority side, then main finale). Each progression line has its own strengths and weaknesses that work for what they are.

Of course, like everything else, scenes in this alternating format have to be arranged thoughtfully. We wouldn’t want the main story to be put on a halt for too long lest the reader too might forget the original plot.

Names

Every year, I come across the same issue. Characters – I know how they act, what they look like, their values, ambitions, and goals. Locations – terrain, population, perhaps a basic map.

But the names, holy shit.

It’s so bad, it’s a hindrance to my writing productivity.

The problem is less the fact that it’s hard to start writing before you’ve thought of one. That’s easily solved by thinking like a programmer and using a solution that, on the manuscript, reads incredibly odd: just create placeholder names that are uniquely identifiable, like $mc, $mc_nickname, $sc1, $sc2, $antag1, etc where required. The symbol is also up to you – you could, say, prefix places with % and items with & if you so wish. Once you eventually decide on a name, you can perform a search and replace.

The actual problem, as hinted, is derivative names, intricate jokes, or other catch phrases that only make sense once you’ve settled down on one. Weeb example, but the most obvious one that comes to mind is Nico from the Love Live! series.[3]

That sort of prerequisite did show up in my project: although I’ve forgotten, Tae’s name I think originally came from Taeswer, so I didn’t have to think too hard for that one.

In another case, I did have to begin with a name of some sort, as that would determine her online handle. That process typically involves spending a few days browsing a database of thousands of baby names on the internet: either CSV files off GitHub, or another site that had an interactive data cruncher built in. Despite the twenty or so hours deliberating on something, the efforts resulted in only one name – Audrey – that I would use for a secondary character.

That’s right, secondary. The main character, Hyphen (stylised as “-”), I haven’t yet decided on a real name. That’s okay though, given her role in the story; she calls herself that by default because (a) anonymity in shady business compels her to do so, and (b) that’s basically how an online handle is supposed to work.

The real reason, actually, is because (c) I’ll take any opportunity to avoid the rabbit hole that is brainstorming given names.

Other names (Tae, Karax, Seneira, Malley) was just me looking at a few Dungeons and Dragons books to narrow down possibilities and/or mixing and matching names of various languages from various kinds of online sources, then vocalising whatever random shit came to mind until one of them stuck. Again, you may have negative interest in D&D as a game like I do, but don’t knock their books until you’ve read through them. It’s a good source of inspiration.

Developers for the earlier PS2 titles of video game series Ratchet & Clank often commented on how the planet names that made it through to their titles all had this ‘Ratchet & Clank-y’ naming sense. I think my character names were similar to that; it’s just got a certain style that I can only guess follows phonetic rules or syllabary.

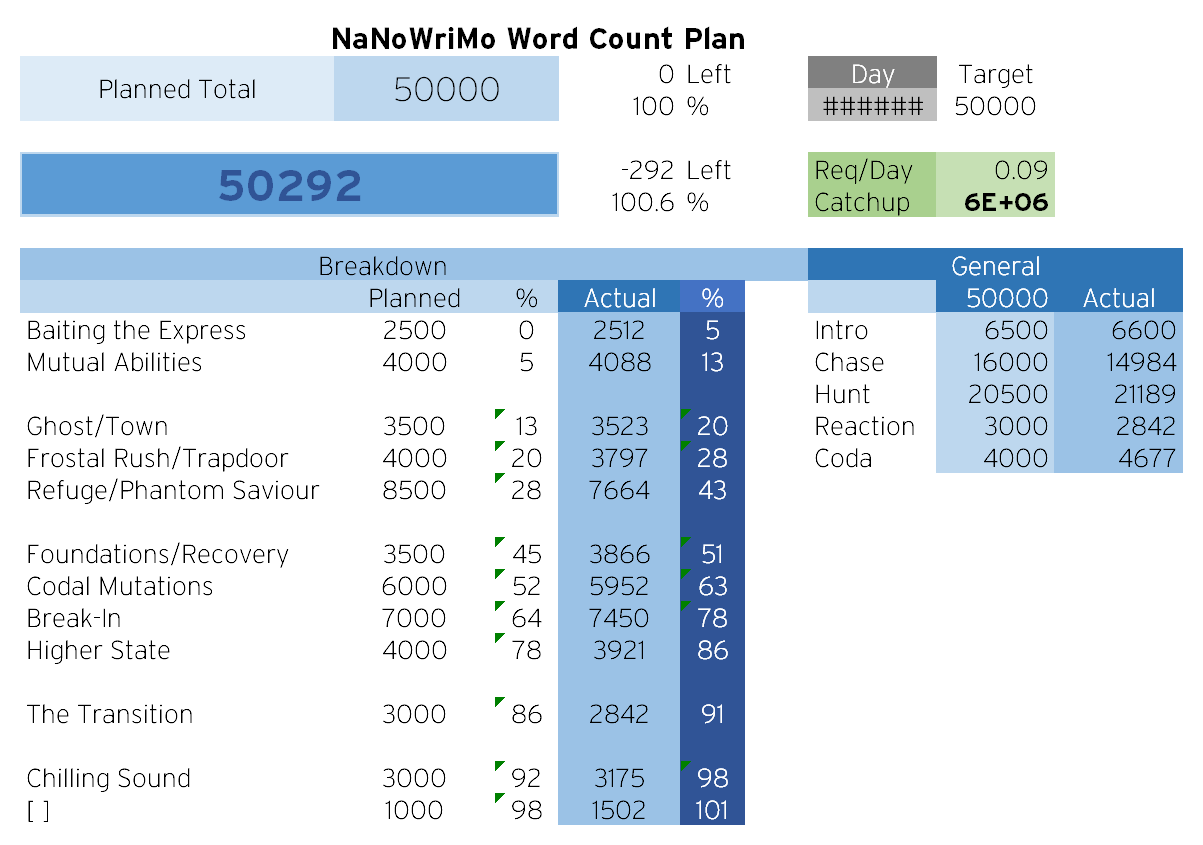

The Spreadsheet

Okay… this is the part we’ve been waiting for.

It started in 2014 where I’d write down my chapters and word count, and it’d give me a progress bar (a small line underneath the cell of the big count), remaining word count average per day, and words I’m behind or ahead of NaNo pace.

When I made the switch to writing on my iPad in 2020 (more portable, less power consumption than a laptop, etc) I had to make a few changes to maintain the features that the Excel spreadsheet couldn’t implement in Numbers.

In 2021, I decided to note down my progress by the day so I could see the trend over time. I also included a few extra calculations such as being able to specify a custom target instead of the average 1 667 – it was how I was able to finish 2022’s project in 20 days, by averaging 2 500.

explanation of the spreadsheet cells

In this spreadsheet, I’ve assigned colours to certain progression concepts.

- Orange indicates real-time. I took this screenshot very close to midnight (some time within the last minute of 00:00), which is why the orange progress bar shows 100.00% and the Catchup value, the number of words needed to stay on time, is −1 706. NaNo’s pacing, according to maffs, indicate on average you need to write a word every 51.84 seconds, hence the extra one word.

- Green is regular NaNo pace. The 24:34 in the screenshot indicates my current position in terms of time, i.e. I was 24 and a half hours ahead (1 707 sounds about right for that). The Progress Time value next to it is that duration represented as a date.

- Purple is my own custom pace, that I can specify in the Manual/Day cell. The 1 724 you see there is a pace of 29 days (so I had a goal to chase) after I missed the 25-day average of 2 000. The number under Manual is the same as Catchup, i.e. the number of words ahead/behind, at the custom pace, and the purple duration above the green one has similar concept.

- Blue is anything to do with my current progress. This covers the top progress bar, word count completed/left, and required words per day at that precise moment in time.

When I plan chapters, I first specify the names of my acts in the General columns on the right, and then split them up into the Breakdown columns on the left. These individual chapter counts are then summed back into General in the first numerical column.

When I begin writing, I write the actual current word count in the Actual column in Breakdown, which is then totalled up per act in General to populate the second numerical column. Everything else is calculated:

- % − is the planning progression before the chapter (i.e. it always starts at 0) because I want to know how many words I have available.

- % + is the actual progression currently as I write, because I want to know how many words I’ve already written.

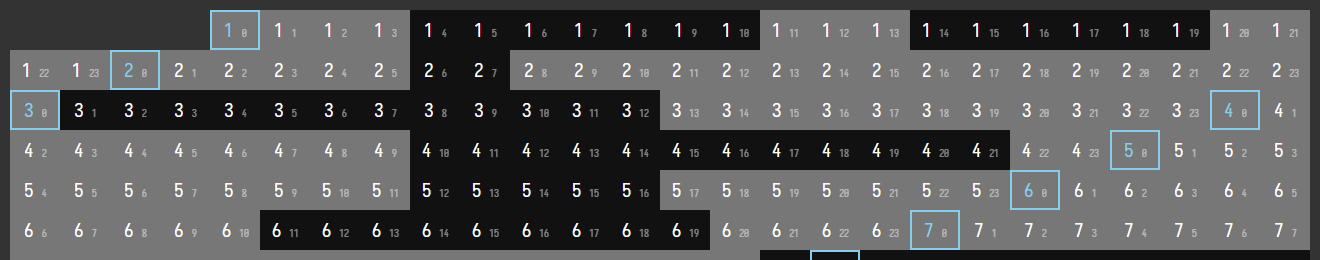

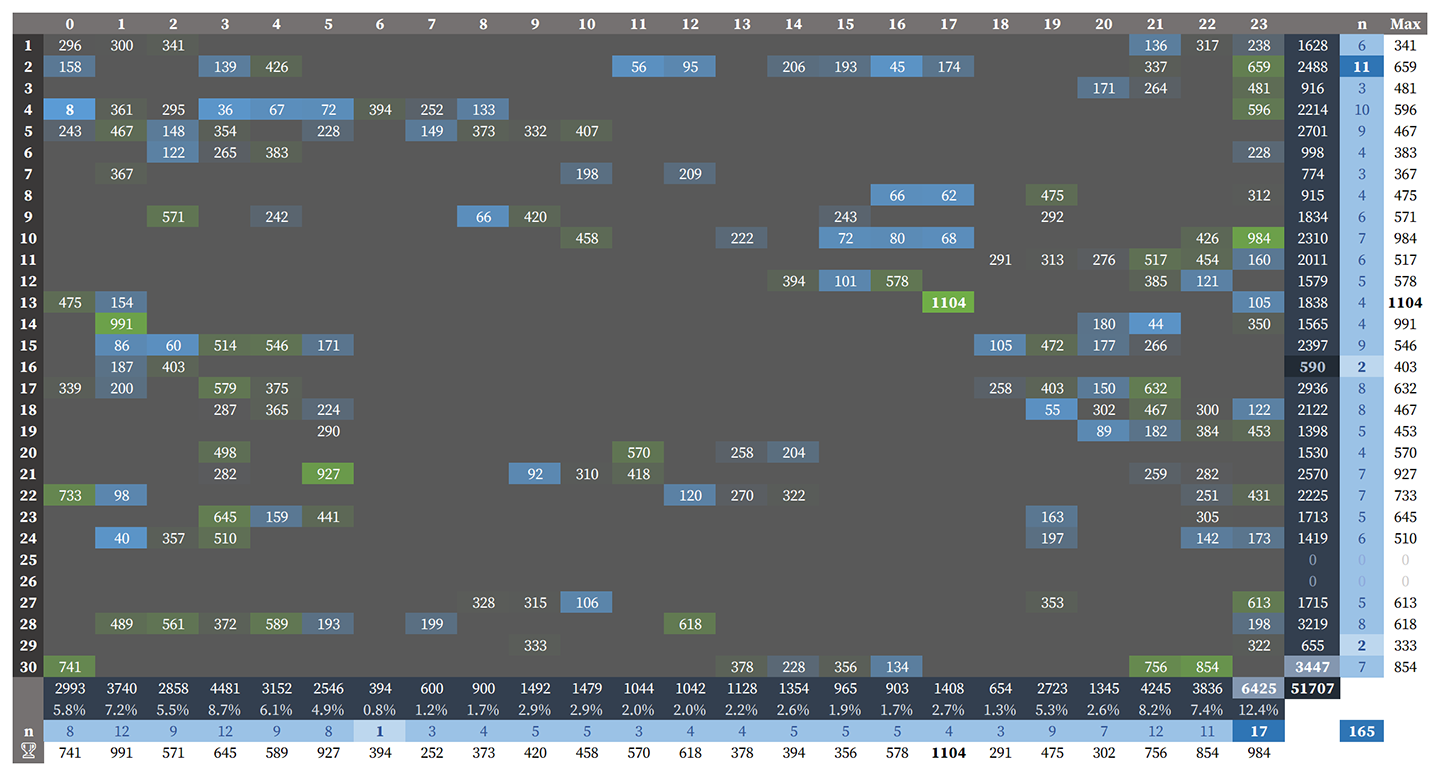

In 2023, I went nek lebel and tracked my progress not only by the day, but by the hour. These were the results.

I’ve anonymised the annotations here and only kept the numbers. Each hour’s spot represents the time that I’ve spent a majority of that hour doing. The colours stand for the following activities:

- Blue, as the numbers imply, indicate when I’ve been writing. Green is extra time spent after I’ve met my target.

- Yellow are times where I had to leave my home (numbers very much a possible thing here too). It generally consists of:

- Being the on-demand personal taxi for my parents so they can attend appointments or activity workshops, at which sometimes I may be able to fit in a few words.

- Shopping for groceries.

- Friends’ events, which included a birthday party and a few gatherings.

- Orange are my own obligations that I have to attend to. These were generally phone or web meetings.

- Black is any time spent sleeping or napping.

- Grey are activities outside of NaNo that I spent more than an hour upon, which happens to be creating ITG content that a few friends really wanted me to have a crack at. (The link is more of an explanation as to what I’m talking about. What I was actually asked to work on can’t be revealed yet, at least at the time of writing this.)

- Uncoloured fields cover practically everything else, a majority of which fall under the most basic physiological layer of the good ol’ Maslow’s hierarchy.

Insights

The moment you look at the above table, you’ll probably notice some few interesting trends, of which the big one involves…

Sleep

I’ve heard of many suggestions that, provided a person had such capacity, one can achieve peak satisfaction with their quality of their life by sleeping whenever they feel like they should: after all, just like your stomach and hunger, you gotta listen to your body. If you feel tired, go rest. More importantly, if not, don’t force it.

A meetup friend of mine living quite a healthy life (no caffeine or alcohol, physically sedentary but makes up for it with lots of brain power, good sleep hygiene habits) occasionally complains about some nights where she goes to bed at ‘reasonable hours’ at midnight to force herself to sleep, incapable of doing so, until 4:00 – only to be woken up by the garbage truck or something.

I can’t help but feel this “suffering” (quote) could’ve been avoided if she just slept at a time where she actually needed to rest. However, of course, not everybody has the luxury to simply sleep whenever – which is why, as someone who has no forced schedule, you might consider the placements of those black boxes to be incredibly erratic.

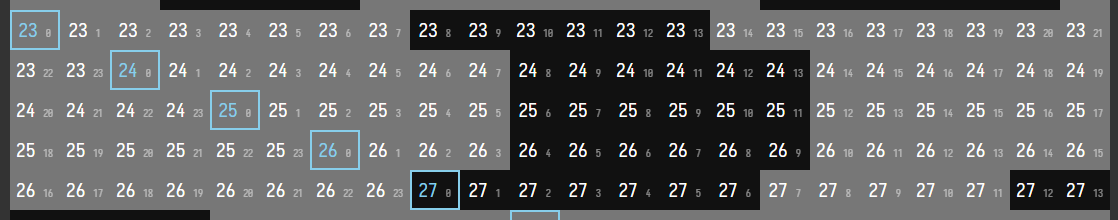

Erratic, you say, but surely you can’t say that diagonal trend for most of the middle half of the month doesn’t follow some kind of pattern.

The first day that I started sleeping normie hours was on the 7th, where I went to bed at 23:00. Whilst I do veer off occasionally, especially near the first few days, I’ve noticed that as each day passed I roughly slept around an hour later and woke up an hour later.

This one-space diagonal trend when plotted on a 24-hour window, indicates that my circadian rhythms prefer to live a day of 25 hours.[4]

In the tables below, I rearranged key days where my sleeping patterns fit better in a different day length window. The highlighted blue cells indicate a date change (i.e. what 24 hours would look like).

Those days where a correlation occurred less than a week long, such as the ones below, might just be trying to shoehorn a pattern in on something that’s otherwise just coincidental. Cope moments at their best!

the first week was 26 hours, the third week 22

What you don’t see here that caused slight concern for me was that months prior I’d sometimes sleep in excess of 15 hours – even if I haven’t been pulling all-day-and-nighters like the kinds that happened on the 6th and the 8th.

I brought this up with my GP and was promptly referred to do a (pathetically performed) home sleep study, whose results concluded that, put frankly… I was just being skill issued.[5]

Normal people “sleeping whenever” should, by average, have a circadian rhythm that’s closer towards 24 and a little bit hours. Close enough, such that exposure to the by-definition 24-hour day of natural sunlight should easily correct for the excess. If the table that you see above suggests 25, it’s without a doubt due to external causes… such as, maybe, working on an iPad (which has a backlight) most days from 20:00 to 6:00 (a time when artificial lighting is typically used)?

To be totally fair, I do have an excuse for that – the place I live in is far from ideal. It’s a spot on a busy street with no air con or soundproofing, which makes work during daylight hours incredibly difficult. Right now as I’m writing this, for some damned reason, my room is 32° (100°) whilst outside is 25° (77°), despite my two windows wide open to try to get some of that cool air in.

The sleep specialist has advised me to start with the ultimate bare minimum of something respectful: sleep before the sun rises, and wake up before the sun sets. That, I’ve eeehhhhh…

Mostly? 🙈 Kept to?

I’ve decided to go back to using a smart alarm (Sleep as Android) to keep my hours in check, and it’s been doing incredibly well. Whilst the first five minutes getting up every single day is absolute dogshit, plus I often snooze spam past my wake up time by up to ~1.5 hours, it’s nothing a bit of fifth grade algebra can’t fix. The most important thing is that I’ve solved my issue of oversleeping.[6]

I’ll probably talk about my adventures with keeping to normie sleeping hours another time. My non-conformity and research into the topic of sleep has made me somewhat of an uncertified search-engine expert on it, much to the intrigue and/or chagrin of my previous workplace’s Slack server.

Writing trends

Here are some number crunching and statistics.

The number of hourly slots, of a total of 720, that I spent:

- Sleeping: 261 (36.3%, averaging 8.7 hours per day)

- Writing: 165 (22.9%, averaging 5.5 hours per day)

- Outside, excluding time spent writing: 68 (9.4%)

- On anything else: 226 (31.4%)

Mins and maxes:

- Most active hour: 23–0, 17 days recorded

- Most productive hour of the day: also 23–0, contributing to 6 425 words (12.4% of my entire project)

- Least active (and productive) hour of the day: 6–7, which was 394 words over just one of the days

- Record productive hour: 17–18 on the 13th, 1 104 words

- Record struggle hour: 0–1 on the 4th, 8 words (LMAO uhh I was distracted with something at the time)

Those points were derived from grabbing the hourly differences in the word count table earlier, to obtain what you see below. For example, the first two hours of progress were 0 → 296 → 596 (as at the start of the hour, i.e. you always begin at 0), so that would show up as 296 → 300 here.

I don’t work by a weekly schedule, so things like ‘least/most x day of the week’ didn’t apply to me; a Saturday I felt was just as equally productive as a Wednesday. The only weekly commitment I had that month was taking my mother to a creativity workshop that she attends every Friday afternoon. Whilst I try my best to make progress in that workshop, there are some… let’s say, enthusiastic individuals, who enjoy conversation. As such, I get very little to nothing done.

It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that the hour just before midnight was my most consistent one throughout the whole month, as that’s when the word count for the day gets locked in. At 12.4% of my project, it beats the 3–4 time slot (8.7%), 21–22 (8.2%), and 22–23 (7.4%).

Otherwise, most days I consistently trudge along for several hours, stopping when I have to live my basic life – more on that in just a moment.

The other slots

Ask anybody what they do outside of work, sleep, and going out with friends/partners – it’s likely you’ll get similar answers.

For me, that consisted mainly of:

- Food related business (cooking, cleaning, planning what to eat, obtaining the ingredients, actually eating). For me, buying food from outside is rarely ever worth the cost, even after considering the effort saved and convenience involved. Big pots of slow cooked meals and curry is the sequel to the broke student’s diet of 875g instant yakisoba boxes and 15-for-$13 KFC Shop A Docket® deals, served with home cooked rice.[7]

- Personal time like gaming, browsing weeb stuff for inspiration (Pixiv, light novels, etc), or just chilling to take a break. Sometimes I’ll do these with my neighbour, either at mine or hers – in which case, I haven’t really considered these as outing time.

- Preparing to go to bed. I’m team shower before bed, and am very pedantic about making sure I don’t dirty it. (Well… okay, you get what I mean.) As in, for example, after coming home, going straight to sleep in my outside clothes – or even worse socks – is a big hygiene no-no.

- Housework. The laundry, carpet, and bathroom ain’t gonna wash itself.

- Time wasted, typically involving distractions like miscellaneous topics on messaging apps, helping parents out with tech support, etc.

There is a reason why 6–7 was my least active hour, outside of actually being asleep at the time. If you’ve read my previous parts on the NaNo project, you may have caught on to something: not surprisingly, I play Genshin Impact. Like most gacha games, Genshin has daily tasks that take about 10–30 minutes to complete. On the Asia server where I play on, a new day starts at 7:00 – and so I tend to cover two days’ worth of dailies by playing before and after this time period.

Writing Progression

A daily writing target of 1.7k words is significant – after all, that is a typical length of a regular uni assignment’s report… and the deadline’s more like a couple of weeks.

Maybe I’m just creatively challenged or perhaps chronically block moment’d, but unless you have The Story To Tell or have a killer outline, the claims going around saying people who work full-time can still “easily find the time to manage” (quote) a full length NaNo… I call bullshit.

I wrote because I had to, not because I wanted to, and it took 5.5 hours on average per day (including weekends) to do so.

If you think that kind of mentality is a turn-off to NaNo, you’re not alone. Many participants realise after a few goes that it’s just not their jam.[8] Some can’t stand writing something that they don’t vibe with, and so rewrite and/or delete it (and as a result, easily put themselves in an incredibly tight position to complete their targets) – but I suspect that comes from a lack of preparation, a situation I’d certainly avoid putting myself in.

One major recurring consequence I’ve learnt writing in ‘had to’ mode to meet a deadline is that it’s not just okay to waffle, it’s encouraged, so that you’re on the safe side of progression. Then, almost always, when you’ve sat down and written something, you’ve already reached your planned target long before you should.

Such is what happened in 2023’s project: the intro, first, and second act, in their entirety, were planned to span 30k words. Instead, I reached 50k writing the intro, first, and half of the second act. Tell you what though – that probably sounds about right; 50k is honestly less of a novel, and more of an extended light novel. My synopsis was based off the expectations of a full-length novel, and my progress seemed to have so far reflected that.

While, yes, I could’ve just wrote normally and stuck to my targets, I always had the risk of getting potentially blocked further down the plan. To me, this was a much greater detriment (negative) versus being able to go into the details of a scene that’s currently in my head at that moment (neutral).

For me, I write as much as I need to, knowing that later on I can cut things out. That’s probably the intended mentality NaNo wanted to teach you, i.e. better to get something down on paper, versus thinking too hard about getting it right the first time – and then worst case scenario – forgetting what you originally thought of in the first place.

Ever tried to remember the details of a dream you really wanted to note down for inspo? It’s like that, but on easy difficulty.

Outputs and Takeaways

“So, are you gonna publish it somewhere, or what?”

Ah yes, a question as common as a dance gamer being asked at the arcade if they’re the best in the country.

My answer: it depends.

Most of the content that comes out of NaNo (or anything really, see my ‘creative jams’ articles) will never see the light of day. However, they may prove useful for the future, just like how 2023’s project was inspired from the year before.

Though, there are always a few snippets of manuscript that I’m proud of to make the cut to show others. Maybe publicly, maybe just with my friends. Usually, it doesn’t happen before I give it a thorough edit – and that only happens if I have the time to commit.

Creative jams (see my site’s writing section tagged so) are an exception to that, since I have a valid excuse to not touch it. Doing so would defeat the original purpose of its time-limit restriction.

But, I think the concept of just putting stuff out there with zero shame is the whole point. One of my former directors at a workplace told me: look, let’s be honest here, a majority of our works are gonna be shit. So, it’d be a no-brainer that one ought to get grinding, right?

That’s true for a hell of a lot of situations: we might not be proud of a lot of the games we’ve created, stories we’ve written, our marketing strategies (a 1% click through rate on an ad is considered pretty damn good), and – whilst we’re on the topic of percentages – dare I say… gacha?[9]

Well actually, it turns out, I’ve been interpreting that advice the wrong way.

The point my director was trying to make was something that I understood in theory, but still coming to terms with practically: it’s not about the grind mindset in the hopes that you occasionally strike creativity gold and produce That One Great Piece.

No, you show everything. Even the shit ones. Why? A few reasons:

- Someone else might actually love it more than you think they do.

- By that virtue, how are you so sure nobody’s going to like it if you haven’t even put it out there for others to see?

- If it is actually shit, how are you going to get that external feedback if you never show it?

- So long as you refine your work, each new one should be better than the previous one. Therefore, technically speaking, the very first submission should be as bad as it gets. (This one is very true – for instance, just look at any illustrator’s portfolio and simply scroll down.)

There is, however, a big difference between shit content and half-assed content. At the beginning, they might be indistinguishable, but ultimately one is a fallacy;[10] if you’re going into something half-assed, then why do it in the first place?

Any true work, done the best you can,[11] is worth showing. Interestingly, this hits home the most when it comes to charting for rhythm games where that gold-in-the-pan attitude is rearing its head again. I rarely share my works with others unless they actually show interest.

I get that creatives have what could almost be called a conflicting responsibility of only showing their best works, since it influences the impression of their portfolio. In contrast, there’s also the common advice that you shouldn’t dismiss and preface your work by saying it’s bad, because (a) that’s subjective, (b) it’s condescending if the work turns out to be actually good, (c) if you insist it’s bad, it already plants an impression for the audience to rather not waste their time on it, and (d) it makes people think you have low self-esteem in general.

Creative stuff, I think, is one of these rare things in life that isn’t subject to negativity bias. As briefly mentioned earlier, if one was to look at any portfolio of a profile on a user created content website, they could browse a lot of awesome stuff first (due to the default order of most recent, where newer works are also presumably better than older ones), and still have a good impression even as they scroll down or occasionally come across the odd one out; positive works have even ground with negative ones, and even still those can be forgiven.

Contrast this against practically anything else – reviews, employees, relationships, opinions – where it only takes a few bad impressions to utterly destroy and cancel out any number of good ones, no matter how small and large; the 0.1% speaks louder than the other 99.9%.

The pitfall is assuming the works we showcase follow this norm of negative bias, when in reality it’s more neutral than we think. That’s especially true when we consider that we’ve typically already place a personal filter deciding who we show our works to: hopefully, those who are enthusiastic about it, and thus more likely to provide productive feedback.[12]

…If only we could approach everyday life like we approach creative works, hey?

And so, with that ending thought, I think I’ve come across my takeaway of NaNoWriMo for this year:

[1] A pretty good programmer analogy is to think of Scrivener like an IDE (Visual Studio, JetBrains products, etc) and Notes like a text editor (Sublime Text, VS Code).

[2] Well, it’s actually not that interesting. Let’s picture a smash scene that is supposed to be interpreted real-time. Consider the duration when it becomes NSFW until it’s not, which we’ll say is 20 minutes. At a reading speed of half a slot per minute, that’s ten slots.

[3] My understanding is, Nico, being the eldest sister in a single-parent family, has the responsibility for looking after her younger siblings, and as such keeping the family together has defined her personality. Her related catch phrase makes use of her name (‘nikoniko’ is onomatopoeic for smiling), and wouldn’t carry as much impact if it wasn’t established.

[4] And yet, we used to joke about how Aunty Anna would play the piana for 25 hours a day. It’s real, folks.

[5] A study of this kind only determines whether I have sleep apnea, which long sleep hours is a known symptom for. Provided I haven’t shown any other obvious signs of sleep apnea (trouble breathing, dry mouth or sore throat, etc), naturally, these results turned back negative.

[6] For the record, I’m using an old Galaxy S6 for sleep tracking, whose aging, bloating battery is starting to become a bit dangerously overdue…

[7] How about the so-called 80 piece, fingernail-sized popcorn chicken? 3-for-$21 large pizzas to last half a week? Man, fast food franchise deals sure brought back the memories.

[8] Though, couldn’t you say that’s the case for real authors, illustrators, mangaka, musicians, and everything in between? Disclaimer: I’m not in that industry, but I have done my fair share of crunch.

[9] This, I can’t relate – out of all games I’ve played, I’ve spent considerably less on online mobile titles, compared to one-off payment ones, or those at the arcades.

[10] As much as I hate it, a more suitable phrase to convey the sentiment of this, is that one of those attitudes is “kinda sus”.

[11] Completely intentional wording.

[12] Actually, y’know, now that I think of it, it’s practically the same as sex. Specifically, the moment where you both take your clothes off. Surely you don’t assume you’re trying for a home run with a complete stranger, unless that’s your kinda jam.